The Bilge Rat offers thanks and says “Orevwa” – by Al Valvano

Dear Patient and Lovely Reader:

Well, I’ve made it. I’m writing this from the island of St. Lucia, on solid ground that does not move unless the rum punch has been particularly effective.

When I last wrote, I was a man adrift, grappling with squalls and the psychological weirdness of being suspended between two continents. Now, I’m a man who has crossed an ocean. The “Bilge Rat” has crossed to the other side. (Wait. That sounds like my ghost wrote that. I assure you, I am alive, just slightly wobbly.)

It’s a strange feeling. For nearly three weeks, the boat was the world. Now, it’s just a boat again, tied to a dock in a place bursting with color, sound, and the glorious smell of things that aren’t saltwater. This is the final chapter of my short, accidental career as an unqualified ocean sailor. It’s my farewell to the Atlantic, to the 1 a.m. watches, and to the constant, gentle sway that I suspect will haunt my inner ear for weeks. It’s time to say “Orevwa,” as they say here—goodbye, for now.

Brown Boobies and Flying Fish

As we closed the final few hundred miles, the character of the ocean began to change. The empty blue expanse started to show signs of life, as if the planet was slowly waking up to greet us. For most of the trip, our main companions were just the flying fish. I’d mentioned finding their sad, dried-out corpses on deck in the morning. What I didn’t fully appreciate was the magic of seeing them alive.

These aren’t just fish that jump. They are legitimate aviators of the sea. They launch themselves from the water at 35 mph—significantly faster than I can run on land—spread their pectoral fins like wings, and glide for incredible distances. They can stay airborne for over 600 feet, catching drafts off the waves just like a hang-glider. They do this to escape predators, but from our perspective, it was a constant, shimmering airshow. At night, they’d occasionally misjudge their flight path and thwack against the hull or, more alarmingly, land on deck with a wet smack, flopping around until a crew member could gently return them to the sea. They were both a source of wonder and a minor, slimy inconvenience—a perfect metaphor for ocean sailing.

But the real heralds of land were the birds. Specifically, the Brown Boobies. As we got within 20 miles of land, they came in droves, circling the boat. Then one of them performed a maneuver that made me audibly gasp. It was soaring about 50 feet above the water, head tilted down, hunting. Suddenly, it folded its wings back into a perfect spear shape and plunged straight down, hitting the water with a violent splash and disappearing completely. A moment later, it resurfaced, shaking its head and, presumably, swallowing a fish whole.

They are the dive-bombers of the avian world, built for aerodynamic efficiency. They look almost prehistoric with their sharp beaks and focused, predatory gaze. Watching them hunt was mesmerizing. It was a raw, unfiltered display of nature, a reminder that beneath the serene surface we’d been sailing over, a constant drama of life and death was unfolding. After weeks of seeing nothing but water, their presence felt like a guarantee: solid ground was no longer just a concept, it was a promise.

Sighting Land

You can’t imagine what it feels like to see land after 17 days at sea. At first, you don’t trust it. You’ve spent two weeks staring at clouds on the horizon thinking, “Is that St. Lucia? No, that’s a cumulus cloud shaped like a taco.”

But then the message popped up on our crew chat: “Land Ho!” We were tracking well ahead of our estimated finish time, so we all rallied up early on deck. On the horizon was a faint, hazy smudge, barely distinguishable from the sky. It was nothing. It was everything.

For two and a half weeks, the horizon had been a perfect, unbroken line separating two shades of blue. Your world shrinks to the confines of the boat, and everything beyond is an abstraction. You know intellectually that there are continents and countries out there, but your senses tell you there is only water. You realize that the world is a damn big place, but so… empty. That smudge on the horizon was the first piece of evidence to the contrary. It was proof that the world was still there.

As we got closer, the smudge grew, darkened, and began to resolve itself into the mountainous, green peaks of St. Lucia. Then came the smell. The air, which for weeks had tasted of nothing but clean, sharp salt, began to carry a new fragrance. It was the scent of earth, of damp soil and faint smoke. It was the perfume of vegetation, of flowers, of people, of life. After living in a sterile, salty environment, the smell of land is thick, rich, and overwhelmingly real.

The Finish

The ARC (Atlantic Rally for Cruisers) has an official finish line, a virtual boundary between two GPS coordinates off the coast of Rodney Bay. As we approached, the mood on the boat shifted. For weeks, the goal was simply to get here safely. We weren’t a racing crew; we were a group of friends (and one idiot bilge rat) helping move a boat.

But it’s impossible to be in a rally with 143 other boats and not feel a flicker of competitive spirit. You start checking the position reports. You discuss sail trim with a little more urgency. You start doing boat math, trying to figure out your ETA versus the boats around you. Suddenly, you kinda care.

We crossed the line around 11 AM, under sail and cruising at a healthy 7+ knots. A committee boat motored near the line, cheering us on. Meanwhile, an irritating photo boat kept crossing in front of us, far too close, despite our shouted commands to clear away. Nothing says “triumphant arrival” while screaming “GET THE ^%#& OUT OF THE WAY” at a stranger.

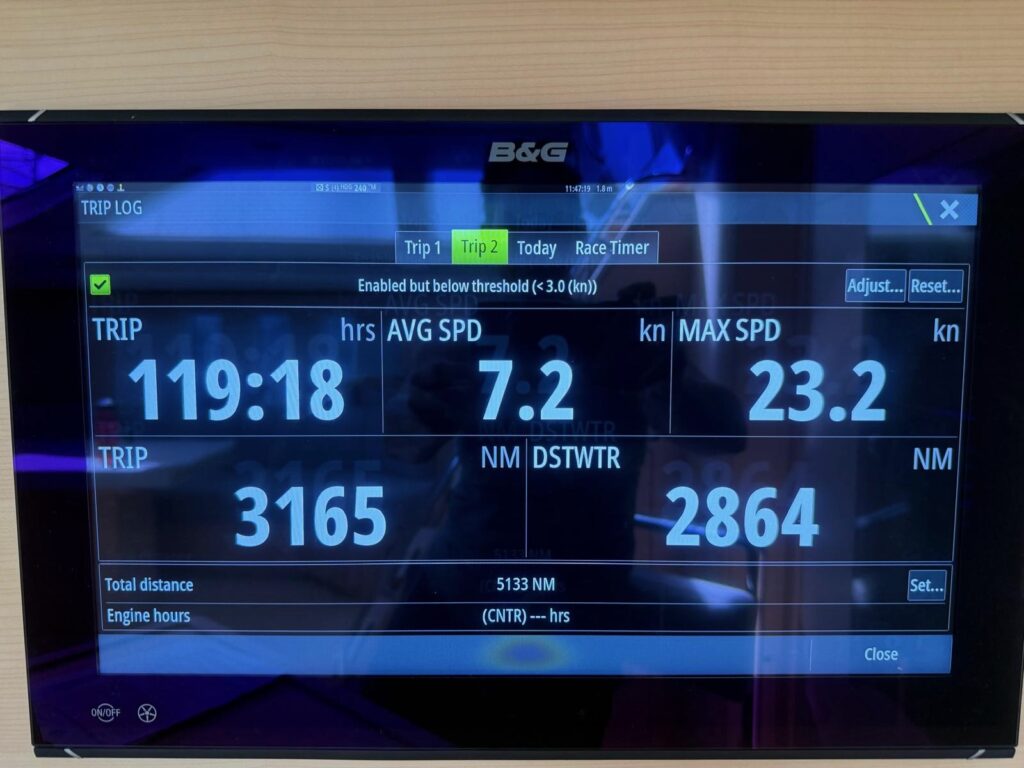

There was no tape to break, no checkered flag, just the satisfaction of knowing we’d done it. The official results: 3165 nautical miles in 16 days, 23 hours. We placed 14th in our class, 34th out of all the cruising class boats, and 54th overall out of 144 teams.

Honestly, that seems like a decent finish for a crew whose primary goal was not to kill each other or sink. But the real victory wasn’t on a leaderboard. The real victory was that we had zero injuries. We had no real boat failures or damage. And most importantly, after so many days in a confined space, we all arrived as friends, still laughing and sharing stories. That’s the win.

Arriving in Port

Sailing into Rodney Bay was sensory overload. After the quiet of the open ocean, the harbor was a cacophony of horns, music, diesel fumes, and shouted voices. Dozens of other sailboats, all adorned with flags from around the world, were already moored. As we navigated toward our slip, people on other boats waved and shouted congratulations.

The moment our lines were secured to the dock, a welcome party appeared with a tray of rum punch and a basket of fresh fruit. Liza was there! They took our picture, officially marking our arrival. I reached for a drink, my body humming with the thrill of accomplishment and the promise of that sweet, sweet rum. We had arrived! We were ready to party!

Uh, no.

We were “under quarantine.” Until we were cleared by customs and immigration, we were not to step foot off the boat. The dock, mere feet away, was a foreign country we did not have permission to enter. So there we sat, on the boat we’d been trapped on for almost three weeks, looking at the freedom just beyond our reach. The irony was thick enough to walk on.

Captain Jay gathered up all our passports and disappeared into the Marina to go wrestle with the bureaucracy.

But I still had rum.

First Chores, Then Fun

About an hour later, Jay returned with our stamped passports. We were legal. We were free. My first thought was of a steak and a beer (I whispered this quietly so as not to offend my vegetarian boat mates). My second was of a long, hot shower where I didn’t have to brace myself against a wall.

But of course, the work wasn’t done. Arriving in port just means the type of work changes. First, we had to connect to shore power and water, a task that involves wrestling with thick, heavy cables and hoses. Then, the real fun began: the deep clean. A boat that has crossed an ocean is covered in a film of salt, grime, and the ghosts of a thousand flying fish. Every exterior surface had to be scrubbed. The interior, which had been a sealed capsule of human existence, needed to be aired out, wiped down, and sanitized.

Then came the laundry. Imagine the accumulated clothes and bedsheets of five people living in a humid, sweaty environment for 18 days. It was a mountain of epic, mildly biohazardous proportions. We bagged it all up to be sent out to a local service that specializes in saving sailors from their own filth.

Finally, after hours of cleaning and organizing, it was time. Let’s explore.

I decided to walk 40 minutes to a local beach for my first real swim in the ocean. The sand was soft and pale. The water was warm, salty, glorious. After 30 minutes or so, I walked back to the Marina and then: drinks.

Finally, the cleanse. The Marina facilities are not the Four Seasons. But—unlimited hot water. A steady, unmoving floor. Space. I didn’t have to squeegee the walls. I didn’t have to worry about the lights suddenly going out (I’m still looking at you, Jay). I stood under the water for what felt like an eternity, washing off 3,000 miles of travel and a smell that I had probably become nose-blind to days ago. It was a baptism. I went in a Bilge Rat and came out a reasonably clean human being. I even used hair product. Nothing says civilization like hair product.

And then, finally, it was time to join the party at the local beach bar with the other boats who had arrived.

What I Learned

So, what does a complete novice learn from sailing across the Atlantic?

First, I have a profound and bottomless respect for people who do this for a living or as a serious passion. From the outside, it looks so peaceful and romantic. From the inside, it’s a stunningly complex exercise in engineering, physics, meteorology, and strategy. Understanding how wind and waves affect the boat, knowing which of the half-dozen sails to use and when to reef them, navigating by instruments when there are no landmarks for 2,000 miles in any direction—it’s an art form masquerading as a hobby. I appreciate the fluid, intuitive genius of a good sailor.

Second, it was a masterclass in teamwork and communication. I’ve led teams small and large my whole career, but this was different. When you’re on a boat in the middle of the ocean, clear, concise communication isn’t just about efficiency; it’s about safety. Every command has a purpose, and every action has a consequence. There’s no room for ego or ambiguity when you’re wrestling with a sail in 30 knots of wind in the middle of the night. You learn to trust your crewmates implicitly.

And as I pack my bags to fly home, I find myself thinking about the things I’ll genuinely miss. I’ll miss the quiet of the night shifts, when the boat is humming along perfectly, slicing through the water under a canopy of darkness. There’s a silent speed to it, a feeling of effortless motion that is pure magic.

I’ll miss the stars—the brightest stars I’ve ever seen.

I’ll miss my friends. We saw each other at our best and mostly-best, and we came through it all with our friendships intact. Jay & Liza are continuing on for the next 16 months to sail around the world. I’m heading back to Seattle. I won’t see them again for a very long time. But I’ll see their dogs, at least, and I like them just as much.

The Bilge Rat Signs Off

And so, the journey is over. This accidental sailor, this Bilge Rat, is hanging up his title. I have successfully crossed an ocean without any relevant skills, knowledge, or qualifications. I have operated a toilet that felt like a garbage disposal, slept in a coffin held together by medieval rope contraptions, and learned what “ease the sheet” really means. I have survived squalls, faced down my fear of being sucked overboard in the dark, and contributed to the mission primarily by not breaking anything expensive.

I came looking for a little adventure and found something much bigger. I found renewed respect for the planet, a deeper appreciation for friendship, and a profound gratitude for solid ground. To Jay, Donna, Hiten, and Melissa: thank you for your patience, your kindness, and for letting this landlubber onto your boat. Fair winds and following seas on the rest of your incredible journey.

As for me? I’m going home. Home. I’m going to hug my beautiful wife too tightly and for too long; to celebrate a quiet rainy Christmas with her and my sweet baby girl who is coming home from Europe for the Holidays; and to miss my boy, who will still be traveling somewhere in Asia.

Godspeed, Welcome. I’ll be watching.

Love from St. Lucia. No more (from me).

Leave a Reply